The project will present the Empress not only as a unique theatrical personality whose perspective of the opera house formed the Russian opera of the second half of the XVIII century, but as a person with a still modern approach to the creation of theatrical productions, where Catherine II acted at the same time as an author, censor, spectator, director, critic and political strategist.

Catherine II is believed to dislike music. She was the one who made her peers and descendants believe that fact. “There are shortcomings in my organization”, she wrote to her long-term correspondent, Baron von Grimm. “I would like to listen to and enjoy music to death, but nothing helps; for me, it’s just noise and nothing else. I would send a prize to your new medical society for someone who could invent an effective remedy for the insensitivity of the harmony of sounds”.

After an opera premiere, the Empress confessed her complete indifference to music to Casanova, who had been seeking favours in Saint Petersburg at the time: “The opera was a great pleasure to everyone, and this made me happy, but I was bored. Music is a wonderful thing, but I don’t understand how one can love it to distraction unless there are no pressing matters or thoughts”.

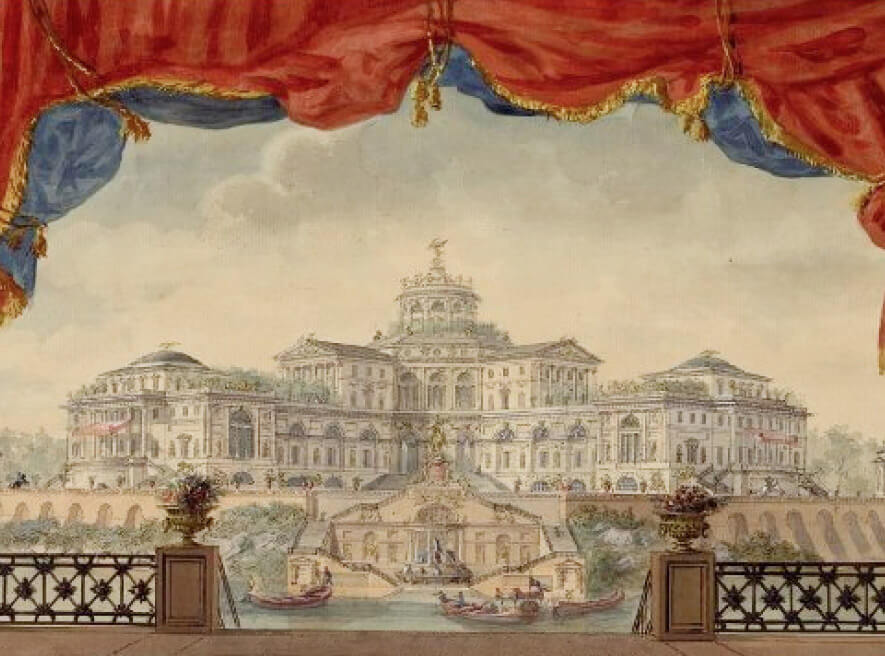

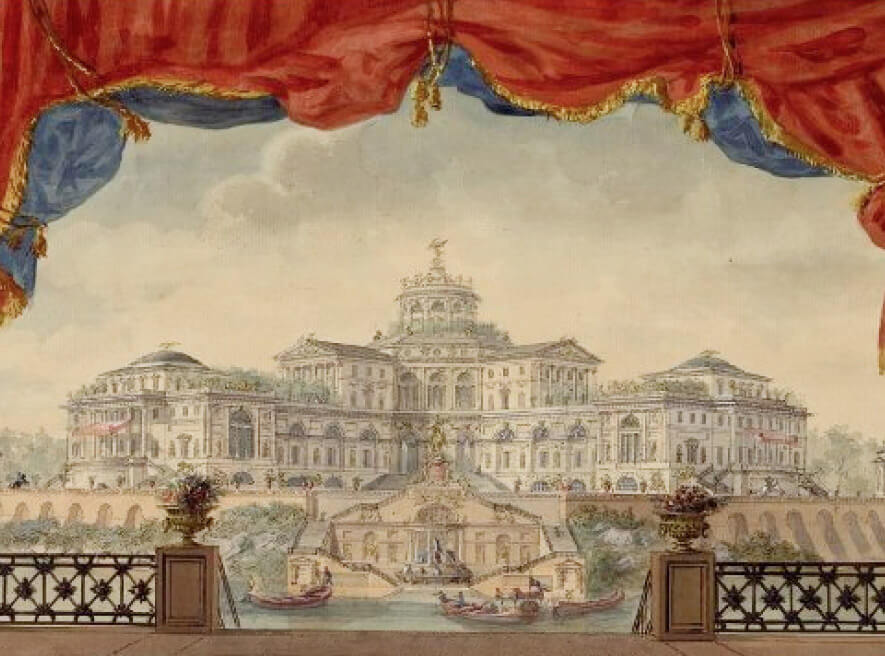

However, at that time, opera was an obligatory part of the ceremonial life at the court, and the monarch could not help but support it. The imperial calendar’s most important and solemn events — name days, coronations, and accession to the throne — were celebrated with a grand and magnificent opera production. Being solemn and easily turned into a relevant political allegory, opera seria became an official genre and visual representation of power. European courts rushed to spend the state treasury to sponsor this “most important of the arts”, brandishing their political ambitions.

This established European practice had been widely accepted in Russia by Catherine’s accession to the throne. However, it was Catherine the Great who, during the 34 years of her reign, managed to turn Saint Petersburg into a brilliant opera capital and make the musical theatre an effective political tool, but also to captivate her subjects, in the words of the same von Grimm, with “musical rage” and theatrical passion.

Being able to choose and listen to intelligent advisers, Catherine II personally selected composers, theatre architects, decorators, and opera stars to invite to the Russian court. As a result, her court troupe engaged the best Italian kapellmeisters of the time, such as Manfredini, Galuppi, Traetta, Paisiello, Cimarosa, and Sarti, had a wonderful orchestra (including horn), one of Europe’s largest choirs and brilliant performers of Italian, French and Russian operas. In September 1791, the ambassador in Vienna offered Prince Potyomkin to hire Mozart “for a short time”, and who knows how the history would have gone if death did not take away the powerful prince less than a month after that and Mozart after three months.

The epoch of Catherine II can be rightfully called the triumph of comic opera — the Italian buffa and the French comique — which gave rise to Russian national opera. It was for the Saint Petersburg court theatre that Paisiello wrote the famous The Barber of Seville and The Imaginary Socrates, the last of which triumphed across Europe and has forever gone down in history as the favourite opera of the Russian Empress.

At the same time, Catherine II launched a kind of “state program” to support the national opera: she encouraged performances by Russian composers in the court theatre. In addition, she sent musicians to leading European mentors to improve their skills. Moreover, she composed six operas, five of which successfully staged during her lifetime, and some performed in the late 19th century. Officially, the Empress authored only librettos and kept incognito and never disclosed her authorship. This open secret helped to enhance operas’ appeal and inspired her friends in Saint Petersburg and Europe to flatter her with crackling compliments to the “anonymous creator” without the risk of being accused of flattery.

Still, Catherine II thought of herself in the theatrical field not as a comedian or even as a full-fledged impresario, but as a statesperson equally talented to pursue her strategic plans and lead the opera, political and historical stages.

At her monarchical desire, the age-old connection between the opera and the court life created a whole range of performances with political and symbolic content and turned the musical theatre into one of the drivers to transform the society and disseminate artistic education, an ideological and aesthetic tuning fork of the program of enlightened reign and at the same time a source of hedonistic pleasure and expression of feelings of the 18th century.

As a loving “mother of the Fatherland and God-given subjects”, the Empress saw her direct duty to “enlighten by entertaining”, foster morals and scourge vices, but also to carefully censor sedition on stage. During the French Revolution, such sedition revealed itself in Beaumarchais’ The Marriage of Figaro and Mozart’s opera of the same title, which were dismissed by some monarchs and even in pretty harmless works. Catherine complained to her secretary, “France has perished because it has fallen into debauchery and vices; the opera buffa has ruined all of them”. Contemporaries understood the meaning of these words, because in Catherine’s epoch, art and life, separated by a ramp, still retained an indissoluble connection that was felt by the 18th century thinkers: once changes happened on the one side, the relevant changes immediately occurred on the other side.

Immersing herself into the system of theatrical production, Catherine II set out to control and regulate it. Having established the theatre directorate for the first time in Russian history, she created an independent structure for managing shows, which functioned like a modern ministry and regulated the budget, the number and staff of court troupes, salaries and pensions, training, student allowances, etc. At the same time, the Empress used to interfere blatantly with the newly-formed institution. She thought theatre to be too serious a political matter to let it out of her control. Nevertheless, her cultural policy helped the imperial theatre take the first step towards emancipation from the monarch and their palace.

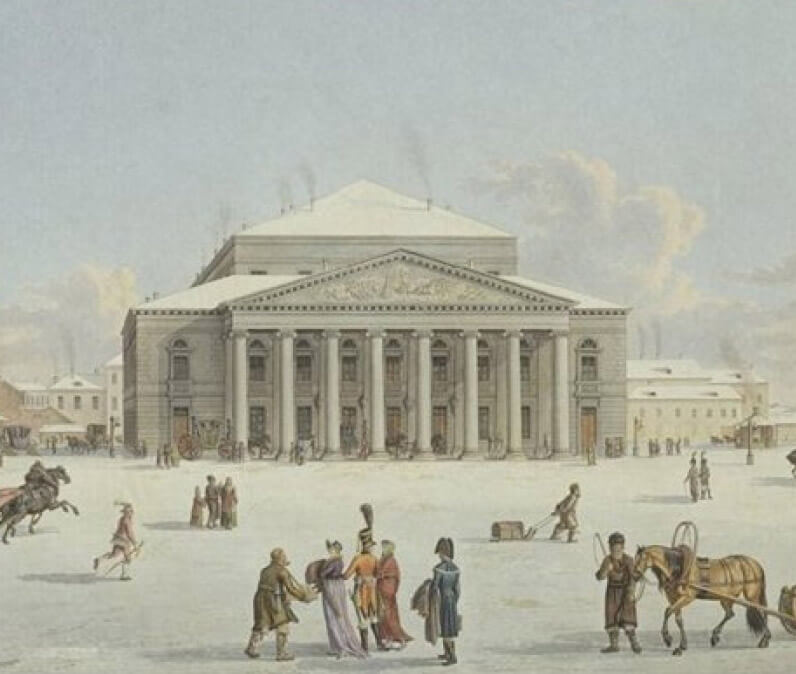

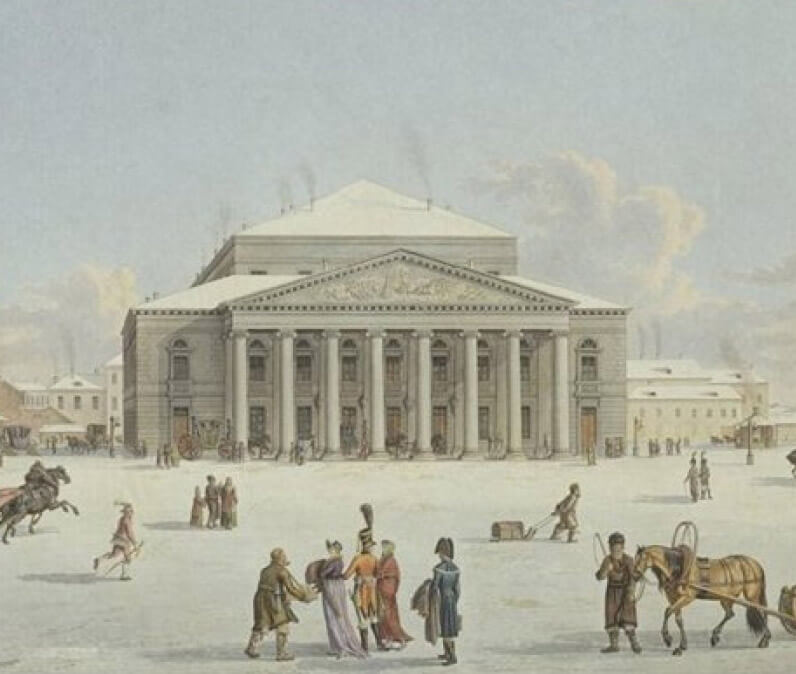

To take imperial troupes outside the Winter Palace, Catherine began constructing the first multi-tiered stone city theatre in Russia. She hoped to compensate the project costs eventually, and the state theatres would stop introducing the monarch’s treasury into exorbitant expenses and begin to generate income. Thus, when the new grandiose theatre was opened in 1783, it was solemnly announced that “Russian, Italian comic and grand operas with ballets commensurate with grand operas” would be presented on its stage. Moreover, six times a year, the performances were given for free: on New Year’s Eve, on Shrovetide, on the name day and the birthday of the Empress and the anniversary of her coronation and ascension to the throne, to treat a diverse city audience to exquisite shows.

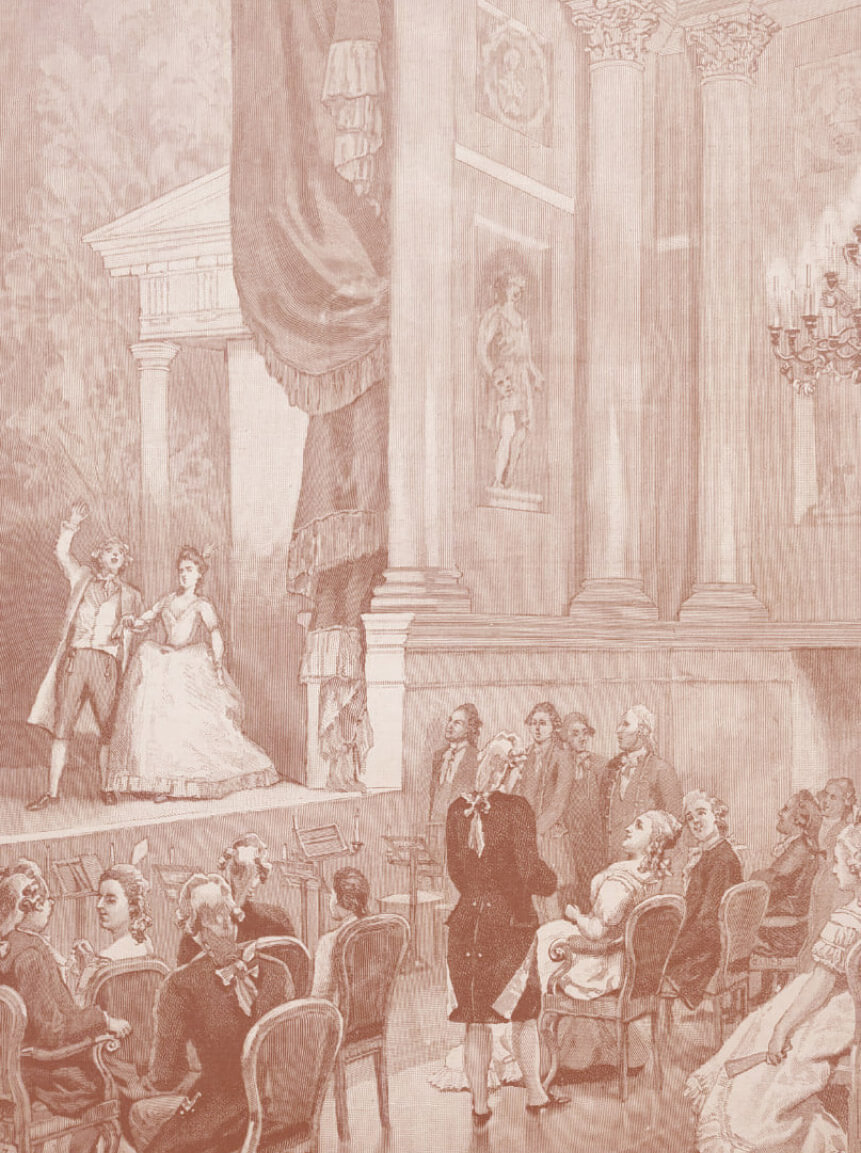

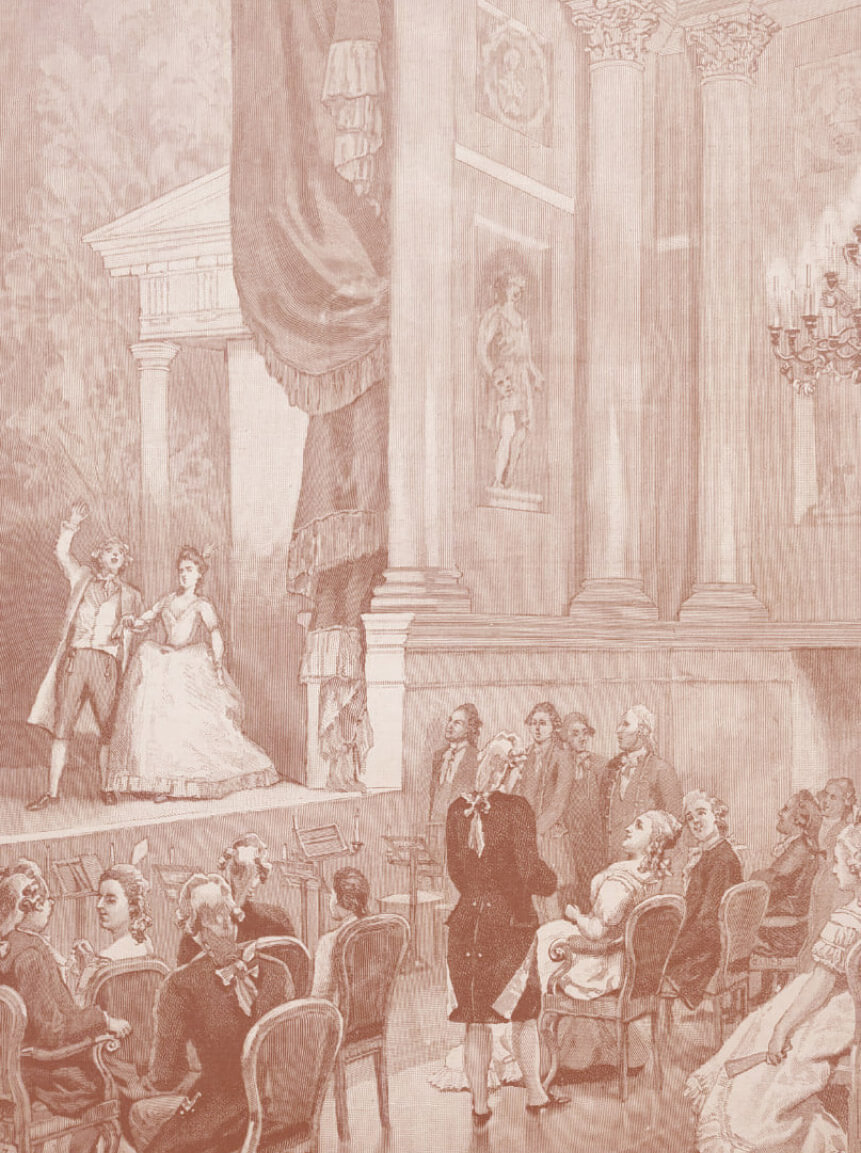

Having begun her reign by encouraging the court ladies and nobles to participate in the palace amateur performances, the Empress was eager to attend performances and concerts in the homes of her entourage, as if giving her subjects her monarchical approval of their personal favour to the theatre. During Catherine’s time, visiting the court opera became a pleasure rather than a social duty. The noble families of Potyomkin, Naryshkin, Sheremetev, and Yaguzhinskiy sponsored their own serf troupes, and many Russian estate owners considered it their duty to “treat” visiting guests with opera and ballet. By the end of the 18th century, according to Pylyaev, “there was not a single rich landowner’s house where orchestras did not rattle, choirs did not sing and where theatrical stages did not rise, on which home-grown artists made feasible sacrifices to the goddesses of art”.

The scope of obsession with the opera during Catherine’s reign was so powerful that it lasted until the end of the century. And while theorists and practitioners scolded the absurdity, boredom and static nature of the decrepit opera seria, and court amateurs sniffed at the simplicity of the low genre of comic opera, the audience heartily enjoyed the virtuoso cadences of visiting guest performers and illusory special effects of the court opera full of hints, wit and voluptuousness.

Russian history knows of no other such examples of the fusion of theatre and government. Individual relapses happened in the 19th and 20th centuries, when monarchs and general secretaries shamelessly intruded with the repertoire and personnel policy. But the following centuries cannot be compared to the scale and lavish generosity of Catherine’s theatrical initiatives. No matter how much the avant-garde directors and revolutionary leaders coincided in their intentions, no matter the annoying enthusiasm with which Stalin sought to create a “Soviet classical opera”, but only in relation to the era of Catherine II, one can refer to Evreinov: “under her rule, the form of government in Russia was close to the theatrocracy”.

Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo.

Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia voluptas sit aspernatur aut odit aut fugit, sed quia consequuntur.

Москва, Дольская д.1, Большой дворец

+7 495 322-44-33